Search

Tag Cloud

Subscribe

10 Things the Galapagos Islands Taught Me in 2018

“It was on the Galapagos in the early autumn of 1835 that Darwin took the first step out of the fairyland of creationism into the coherent and comprehensible world of modern biology,” writes eminent British naturalist Julian Huxley in his 1966 study titled Charles Darwin: Galapagos and After, “for it was here that he became fully convinced that species are not immutable—in other words, that evolution is a fact.”

And ever since Charles Darwin wandered the Galapagos with his eyes wide open in wonder, the archipelago has played an increasing role in the world’s trove of natural history facts and science findings. By some accounts, it’s said that more scientific papers have been published about the Galapagos than any other group of oceanic islands except Hawaii. It could be argued that no area on Earth of comparable size has contributed more to environmental knowledge than the Galapagos Islands.

Little more than 100 years after Darwin’s footprints in the Floreana, Isabela, San Cristobal and Santiago sands—in the 1960s—a flow of ecotourists to the islands began. The new visitors, in the hundreds of thousands, were attracted by reports of walks among and close-up encounters with unafraid blue-footed boobies, flamingos, giant tortoises, and land and marine iguanas.

During 2018, I have had the pleasure of writing about this very complex place of scientific endeavor, learning, and ecotourism benefits and struggles. The experience has taught me several things—not only about the Galapagos Islands themselves, but about life in general. So, at the end of the year, in this reflective time, I’d like to present just 10 of the lessons that Ecuador’s first national park and one of the United Nations’ initial World Heritage sites has taught me in the past 12 months:

1. Pay attention to the small things in life. As the renowned American author Kurt Vonnegut once said, “Enjoy the little things in life, because one day you'll look back and realize they were the big things.”

In April of 2018, I reported on a 2015 research study that identified an innocent-looking parasitic fly, Philornis downsi, introduced from mainland Ecuador, that’s preying on the islands’ birds. Alongside other risk factors—such as habitat destruction and predation by other invasive species, such as rats—Philornis downsi could be the final blow that causes some bird species to completely disappear from certain islands.

If something as small as a fly can change the Galapagos forever, we should never disregard what’s tiny; what’s minuscule can be powerful.

2. Sometimes the most exciting things happen right under our noses. We usually think of evolution in terms of long time lines, with the beginning mark dated eons ago. But in 1981, two evolutionary biologists working on Daphne Major noticed the arrival of a non-native bird: a large cactus finch. In just two generations, the bird’s offspring had developed into a new species, confirmed by genetic studies.

Surprisingly, monumental things—such as the complete evolution of a new life-form—do happen right in front of us, within our lifetimes.

3. Don’t be afraid to dive into what at first looks like trouble—if it will get you to a positive end goal. In July 2018, I wrote about a recent study that showed that great frigate birds are the only birds known to fly deliberately into high-altitude clouds, where there are turbulent winds and freezing temperatures.

Why? They do it in order to use the air currents needed for sustained soaring.

Sometimes, you have to be willing to take a brave step in order to live your best life.

4. All aliens aren’t bad. Coffee, an introduced plant to the Galapagos, may turn out to be the rescuer of the endemic Scalesia trees, which—since the arrival of humans in the islands—have been largely wiped out.

Coffee plants can serve as barriers for protected areas against highly aggressive plant and insect species. They grow well in shade, under Scalesia’s cover, producing an economic incentive for reforestation. The water requirement for growing coffee is considerably less than it is for many other crops, and the by-product from coffee’s pulping and fermentation process can be used for composting in organic agriculture.

At times, there’s a lot of good that can come from allowing aliens into our midst.

5. Tourism isn’t all good—or all bad. When tourists visit popular hot spots in large numbers, they can pack in some problems. In the Galapagos, as tourist numbers soar, so do the number of airplanes and cargo ships arriving from the mainland, carrying food and other supplies. Such vessels are the primary vectors for new, potentially catastrophic invasive species. In addition, rapid tourism growth strains the limited natural resources of the islands and has led to an explosion of new businesses that specifically cater to tourists. But ecotourism also brings a great economic benefit to Ecuador, helping local residents make their livings.

Issues are seldom black-and-white. Creating a positive, sustaining ecotourism model that helps and doesn’t harm is hard work. But it’s worth doing, so that the world can simultaneously protect and enjoy the one-of-a-kind Galapagos Islands.

6. Museums are not only keepers of the past; they’re keys to the future. In May 2018, I brought you the story of a new species of tortoise living on Santa Cruz Island that came to light with the help of museum specimens. From bone remnants housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Zoological Museum, scientists at Yale University were able to identify a giant tortoise that is so genetically different from the rest of the island’s giant tortoises that it deserved its own species designation: Chelonoidis donfaustoi. Today, there are about 250 of these animals living in the arid, eastern interior of Santa Cruz.

Far from being stuffy institutions that simply hold relics of the past, museums are ripe for new discoveries.

7. The past is still a frontier. Similarly, in a larger sense, the same article showed that the past is still an unknown realm. Recently, museum specimens showed that a vermilion flycatcher on San Cristobal was a new species and not a subspecies as previously thought. By using molecular data from samples of museum specimens and advanced genetic techniques, scientists determined that the San Cristobal vermilion flycatcher (Pyrocephalus dubius) is—or, more precisely, was—genetically and morphologically distinct from its nearest relatives. Sadly, its last sighting on the wing was in 1987.

The past is full of the as-yet-unknown and countless untold stories.

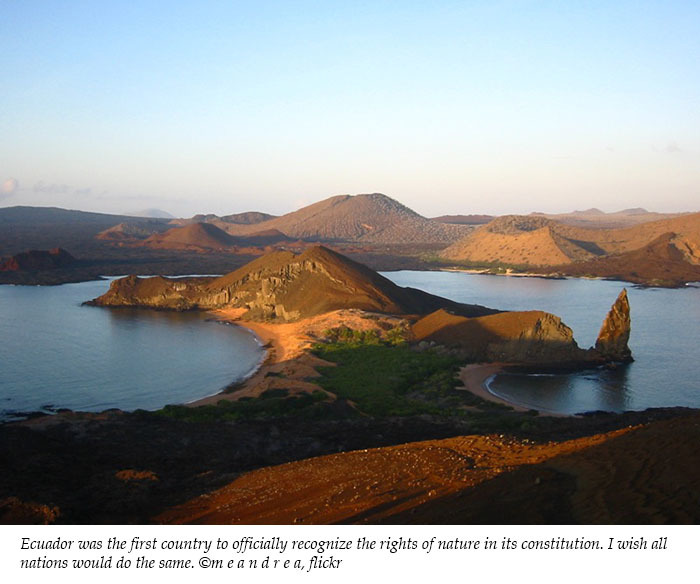

8. We must recognize the rights of nature. Most nations treat nature as property. But Ecuador was the first country to officially recognize the rights of nature in its constitution. Under the law in Ecuador, Rights of Nature articles acknowledge that “Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.”

If all nations of the world shared that sentiment, we may have avoided the current sixth mass extinction.

9. Climate change is real, and it’s here. On March 14, 2018, World Wildlife Fund, Australia’s James Cook University and England’s University of East Anglia published a report titled Wildlife in a Warming World that stated that as much as half of all the wildlife species and 60 percent of the plant species in the world’s most biodiverse areas could be at risk of extinction by 2100 if stronger efforts aren’t taken to combat climate change. The Galapagos Islands are one of those named, biodiverse regions.

Although the facts of climate change aren’t something I newly learned about in 2018 (I’ve been writing about the dangers of global warming since 2010), this year has proven, once again, that we’re doing little to stop our rapid descent into the catastrophic effects of climate change.

It bears repeating—yet again—this year.

10. We still have a lot to learn about this world. Just when you think that everything there is to know about nature has been analyzed, probed, photographed, recorded, researched and tracked, new discoveries pop up. For example, recently a new hammerhead shark nursery was discovered in the Galapagos. And just weeks ago, it was announced that researchers may have found where the female hammerhead sharks that live near Darwin and Wolf Islands go to have their pups.

It appears there’s no end to what we still don’t know.

My advice to you is to stay curious in 2019 and follow the science. Much like Charles Darwin did a century ago, keep your eyes wide open all the time; doing so can lead to some wondrous things.

Have a very happy New Year,

Candy

Feature image: Flamingos can be found throughout the Galapagos Islands, but larger colonies are visible on three of the islands Charles Darwin visited: Floreana, Isabela and Santiago. ©alh1, flickr