Search

Tag Cloud

Subscribe

Coffee and Conservation: Can an Introduced Plant Do Good in the Galapagos?

People visit the Galapagos Islands for a number of reasons; among them are the fearless wildlife, the one-of-a-kind landscapes and the wonders found underwater. Few come for the coffee.

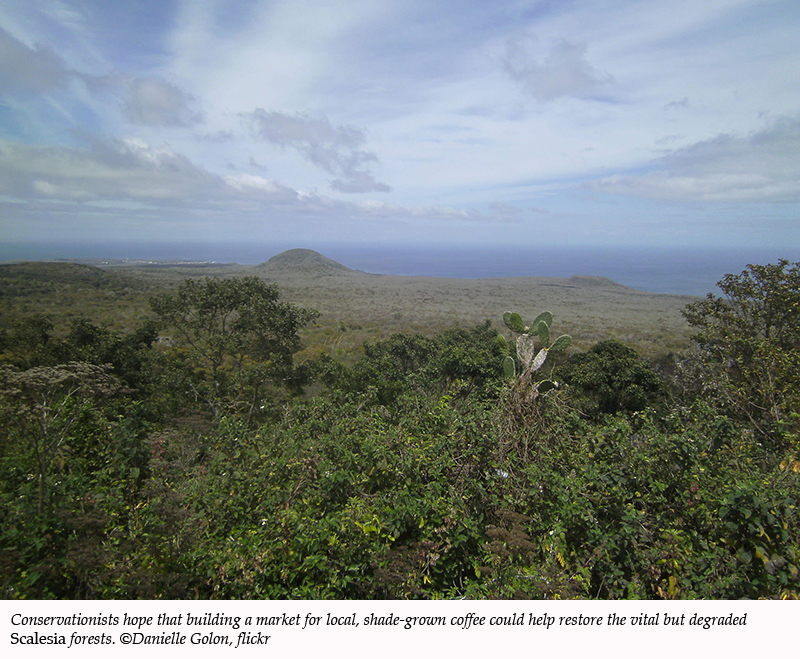

But perhaps they should, because coffee could turn out to be the rescuer of the endemic Scalesia trees, which—since the arrival of humans in the islands—have been largely wiped out. Many birds and insects that are vital to Galapagos ecosystems depend on the trees for at least some part of their life cycle. In fact, the larvae of one species of moth (Hellinsia nephogenes) feed only on Scalesia. Without the trees, the moths disappear, which causes a reaction up through the food chain that reverberates throughout the islands.

But can an introduced plant—coffee—possibly be good for the Galapagos?

Perfect place for the coffee plant

Sometime around 1870, the first coffee seeds were brought to the Galapagos Islands from French colonies in the Caribbean. These seeds were of the Bourbon variety, which remains the main type of coffee grown on the islands today. Forty to 50 years ago, emigrants from the Loja Province of Ecuador introduced other varieties of coffee, such as Catuai, Caturra, Sachimor and Typica.

To the early settlers, the Galapagos seemed to be the perfect place to grow coffee. The islands are one of the few regions on Earth that can sustain two coffee harvests per year: February to March and November to December, thanks to the Humboldt Current.

The cold, low-salinity Humboldt Current flows north along the west coast of South America, from Chile up to northern Peru and then out to the Galapagos Islands. It brings with it cool marine breezes that bring down land temperatures. So, although the islands receive intense sun, they don’t receive blistering heat. In fact, the climate is similar to what you’d expect at 4,000 to 4,250 feet above sea level. Even in the hottest months, the temperature rarely reaches above 86 degrees Fahrenheit. And in July to September, the dry season, it can drop below 68 degrees Fahrenheit. This is part of the reason why low-altitude coffee from the Galapagos Islands (usually grown at 2,400 to 2,800 feet above sea level) can taste and roast like high-altitude coffee from other parts of the Americas.

Soil quality is another key advantage to growing coffee here: the Galapagos Islands were created by the frequent eruption of volcanoes millions of years ago. The layering of these—at the time, underwater—volcanoes built up until they emerged from the ocean. Volcanic soil is rich in nutrients, such as nitrogen, which is particularly important for growing coffee.

Today, the main coffee-producing islands are San Cristobal and Santa Cruz. All Galapagos Islands coffee has to be organic, since the Ecuadorian government banned the majority of pesticides and agrochemicals in the Special Law of 1998.

Problem perc or conservation crop?

Although coffee is an introduced plant species in the Galapagos Islands, it provides an important opportunity for local farmers. As fisheries become depleted, organic agriculture becomes a replacement source of income for island residents.

Organic crops also help to reduce the need for imported food, and thus they minimize the introduction of invasive species that arrive in outside shipments. Additionally, according to The Friends of the Galapagos Organizations:

- Coffee is a nonaggressive species that can serve as a barrier for protected areas against highly aggressive plant and insect species.

- Most coffee plants grow much better in shade. Coffee production, therefore, meshes well with conservation, ecological, reforestation and restoration initiatives, especially those involving Scalesia. Coffee grows well under this native tree’s cover.

- During the production cycle, coffee’s water requirement is considerably less than it is for many other crops. Even when considering the water that is often used in postharvest processing, coffee’s “water footprint” is less than that of many lucrative alternatives.

- The by-product from coffee’s pulping and fermentation process can be used for composting in organic agriculture.

There are obstacles to growing coffee in the Galapagos, of course. Protecting the islands’ ecosystems involves balancing land and water use, inhabited and uninhabited areas, and the conflicting needs of the economy, nature and people.

For example, harvesting coffee requires intensive labor. While that represents an opportunity for local residents, if not managed carefully it could result in pressure to bring laborers in from the mainland, stressing the Galapagos’ other resources.

And if increased coffee production is carried out in the islands, it will be important to make sure that it proceeds in an environmentally sound manner, such as certifying that it is shade-grown and that it remains organic. Producers will also need to be willing to support inspection and quarantine measures to avoid the introduction of coffee pests into the Galapagos.

Savor the sip

Those who have had the pleasure of tasting Galapagos Islands’ ecosystem-restoring, organic, shade-grown coffee say that its flavor is truly unique. But its sweetest quality may be in knowing that sipping it saves Scalesia.

Feature image: Currently, most of the coffee in the Galapagos Islands is grown on San Cristobal and Santa Cruz Islands.