Search

Tag Cloud

Subscribe

Flying into the Clouds, the Great Frigate Bird Way

You’ve probably dreamed that you’re able to fly. That’s because it’s one of the most common dream themes that we humans experience; and, for the most part, flying dreams are happy ones. In your slumber, as you effortlessly defy gravity and soar into the clouds, you feel as if you’re Superman. For the first time in your life, you taste true freedom—escape from the pressures of the real world that’s below you, there on the ground. You never wish to be earthbound again.

Then, you wake up.

Unless you’re a great frigate bird, that is. While scientists have known for some time that frigate birds can stay aloft for several days, it wasn’t until just two years ago that they discovered just how long the birds could go without landing—and how they did it.

Tiny, 10-gram transmitters

Great frigate birds (Fregata minor) grow to more than three feet in length and have a wingspan measuring 7.5 feet. They have the lowest “wing load” of all birds, which means that no bird has a higher ratio of wing surface area to body weight. They nest on islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, including on the Galapagos Islands.

Despite being seabirds, however, great frigates do not have water-repellent feathers, so they can’t stay afloat on the water for long and avoid landing on it. To find food, they must fly for long distances and periods of time, hoping to sail over a fish-feeding frenzy on the ocean surface or to spot small fish that leap out of the water to escape larger fish. Sometimes, they feed by harassing other birds in flight until they release whatever fish they’ve caught, allowing the frigate birds to then snatch the prey from midair before it reaches the water.

But knowing that frigate birds undertook long ocean flights didn’t explain how the birds managed the feat. So, biologist Henri Weimerskirch at the French National Center for Scientific Research and his colleagues decided to outfit 50 great frigate birds with solar-powered, ultralightweight transmitters that attached to the napes of the birds’ necks. From 2011 to 2015, the tiny data-loggers measured acceleration, altitude, GPS coordinates, heart rates and wing-beat frequency.

Sustained soaring

What Weimerskirch and his team discovered was groundbreaking. According to the study’s results published in the journal Science on July 1, 2016, great frigate birds fly for up to 56 days without landing, reach altitudes of more than 2.5 miles, cover more than 300 miles per day on average and flap their wings just once every six minutes or so. One of Weimerskirch’s tagged birds soared for 40 miles without a single wing-flap. The altitudes these tropical birds achieve were especially surprising: two-and-a-half miles are more than 13,000 feet, higher than some of the peaks in the Rocky Mountains. No other bird flies so high relative to the sea surface.

You would expect that staying aloft for almost two months at a time and flying so high and so far would take a huge amount of physical energy. But the instruments monitoring the great frigate birds’ heartbeats showed that they were hardly working. They had figured out how to go to faraway places quicker by siphoning off energy from somewhere else: the atmosphere.

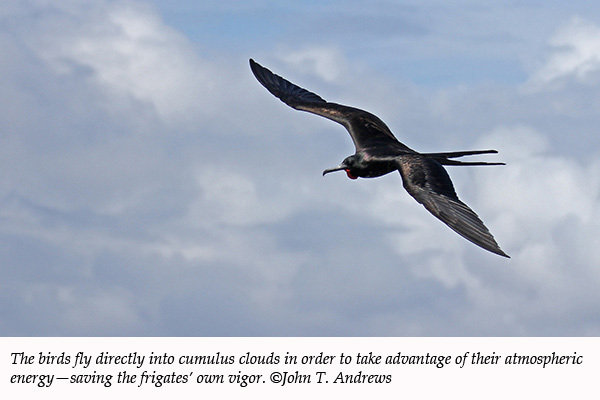

For such sustained soaring, the birds take advantage of the unique weather patterns in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Throughout the year, huge patches of the ocean remain relatively windless. Great frigate birds tend to linger around the edges of these doldrums, which are sprinkled with puffy, low-lying, cumulus clouds. Beneath these cotton-looking billows, there are updrafts the birds can ride to rocket themselves into the air, ascending 5,249 feet without flapping their wings and sometimes shooting upwards at rates of 13 to 16 feet per second. Once at the higher altitudes, the birds can then glide downward for long distances, flying with side winds to achieve high ground speeds, before hitching a ride on the next updraft. It’s like riding a roller coaster.

In order to use these helpful air currents, the birds weren’t afraid to fly straight into the clouds, and they did it intentionally—another big surprise for the researchers, in view of the turbulence within clouds and the freezing temperatures at such high altitudes. In fact, Weimerskirch has stated that the great frigate bird is the only bird known to deliberately enter into a cloud.

Near the doldrums, the birds spent only around 10 percent of their time looking for food. For most of the time, they soared from cumulus cloud to cumulus cloud, favoring the places where very little flapping was required to stay airborne: somewhere between 98 and 6,562 feet. Only when foraging for food, which is much more energy-intensive, did they drop down to elevations below 98 feet.

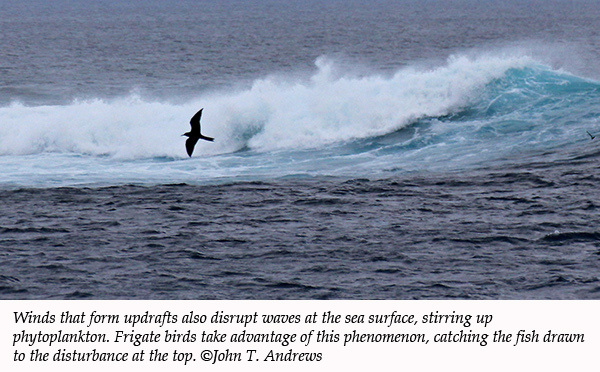

The study also showed that great frigate birds capitalize on a lucky coincidence. Winds that form the updrafts also disrupt waves at the sea surface. And when the wave pattern is interrupted, deeper water rises, carrying with it organisms—such as phytoplankton—that attract small fish. The small fish attract bigger fish, which creates the feeding frenzy that frigate birds need for dining.

Frigate bird flights of fancy

Great frigate birds may be our dream avatars. They seem to fly over the landscape effortlessly, hopping off their atmospheric, amusement park ride only to dip down for a quick bite. Then they jump back on again, to bounce about in the clouds.

If only, just once in a while, our inner Supermans could manage that.

Feature image: Great frigate birds are large, with long wings and deeply forked tails. Females have a white underbelly. ©John T. Andrews